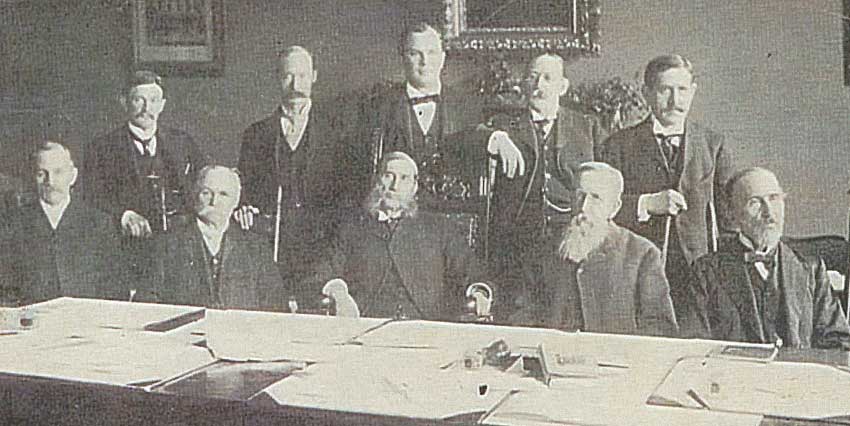

Association Founders

By the early 1910's, city mission—or rescue missions, as they were starting to be called—had come of age. The first North American mission, the McAuley Water Street Mission in New York, was 41 years old in 1913. Many men and women had gone out from there to start other missions across the United States and Canada and around the world. Thirty of these men and women saw the need for sharing their expertise, helping new directors get established, training, and spiritual renewal in the International Union of Gospel Missions (today, Citygate Network).

Many of the names on the Articles of Incorporation are not quickly recognized. Their stories are probably lost to history, and the missions where they served closed. “Rescue mission men were not known to keep complete files,” wrote former IUGM Board president Leonard Hunt in the 1964 work, The IUGM History and Future. Several, though, were men and women whose vision for ministry would still impress us today. “They were highly individualistic,” Leonard wrote “They were as independent as could be, giants in their own areas. Yet in spite of this individualism, they had heart-warming fellowship together around the cross of Christ, and the common cause—rescue.”

What a challenge these men and women had before them! Their missions were not necessarily large when they banded together to form the IUGM. They didn’t have huge budgets or staffs to operate their own ministries while they worked for another organization. But they had a vision of an organization that would assist, train, encourage, and challenge rescue mission leaders in the United States and around the world. More than 100 years later, that organization started in the office of the Water Street Mission is still advancing—still seeking the provide education, fellowship, and service to the men and women who are ministering in the neediest parts of our cities.

Founders: In Their Own Words

Sidney and Emma Whittemore

Sidney Whittemore and his wife, Emma, were wealthy, cultured, church-going people who lived in New York City. In 1874, they paid a visit to the Water Street Mission to see what their giving was supporting.

“I…went down to Water Street, feeling that I was such a big one in church life that I knew everything, and to go down and shake hands with Jerry McAuley and his wife—why, yes, I would, and encourage him in that way,” Sidney later said, according to the 1907 book, Jerry McAuley: An Apostle to the Lost edited by R. M. Offord.

The refined couple was sorely out of place among the needy individuals attending the service, but when the altar call was given, husband and wife held up their hands and went forward to kneel with the crowd of broken men. Sidney, who had planned just to sit and look on, increased his nights at the mission until he and Emma were with the McAuleys five out of seven nights each week. He served on the board of the Cremore Mission. In The Romance of Rescue, William Paul quotes a 1921 association document that stated the IUGM was a “child of the heart” of Sidney. As the first board president of the IUGM, he had a vision for furthering the cause of rescue.

Emma Whittemore said that before her conversion she was of that character of church people so prevalent—“a card-playing, theater-going, dancing Christian,” wrote Samuel H. Handley in the 1902 volume, Down in Water Street. When she first visited the mission, “it was with the district understanding that I was never to go to such a place as that again,” according to Jerry McAuley: An Apostle to the Lost. After going forward at that first meeting, Emma not only helped her husband, but also organized the Door of Hope for lost and helpless girls. She went on to establish more than 50 Door of Hope missions in other cities, and served as the second elected IUGM president, carrying on the vision of her husband after he was gone.

John and May Wyburn

John Wyburn, an Englishman, came to America to take charge of his brother’s business. When his brother died in 1882, John inherited a large share of the business and a generous cash legacy. Three years later, despondent with life, he withdrew his money and began drinking. He ended up in the Bowery of New York City, penniless. A convert of the Water Street Mission gave John a referral to Samuel Handley, the mission superintendent. John didn’t mean to stay at the mission. He planned to hit Handley for a “loan” of $10 and get out of there quickly. Handley invited him to stay for the service, and when that convert stood and gave his testimony of how God delivered him from drunkenness, John surrendered his will to the Lord.

He forgot about going back to his business. Instead, he worked as a clerk at a lodging house and returned to the mission every night of the week. In 1896, he became superintendent of the Bowery Mission; there he met a pretty young volunteer, May, who later became his wife. Three years later, he returned to Water Street as the assistant to the superintendent. When Samuel Handley died in February 1906, John became the superintendent, serving until his death in 1921, according to Arthur Bonner’s 1936 book, Jerry McAuley and His Mission.

“On at least three occasions, Mr. Wyburn was approached just before the annual business meeting and urged to accept the nomination for the presidency of this organization,” May Wyburn wrote in her 1936 work, But Until Seventy Times Seven. “But he declined fearing it might take him away too often from his work in Water Street, which always took precedence over everything else.”

Sara Wray, superintendent of the Eighth Avenue Mission in New York City, spoke of John Wyburn’s love for men at his memorial service, according to But Until Seventy Times Seven. “I shall never forget a convention of rescue mission superintendents in a distant city two or three years ago [1918 or 1919] where Mr. Wyburn and other superintendents, myself included, were. We heard eloquent addresses, but there was just one thing that really gripped me…Just one sentence, uttered with such thrilling effect on my soul…’We never give a man up,’ said Mr. Wyburn. Others may weary, other may say it is of no use, others may speak of wasted time and wasted money, but he, never. (He) knew the love and power of the Good Shepherd Himself.

John R. McIntyre

John R. McIntyre, also an Englishman, was a member of the Royal Exchange in London. He worked his way to the head of a company that employed more than 1,000.

He came to America for a new start, to escape his drinking problem, and soon became head of a department in the Wanamaker store in Philadelphia. But liquor again led him to the gutter. John walked six miles to Germantown, and became the first convert of the Whosoever Gospel Mission, founded by William Raws. John later became the mission’s superintendent, giving 50 years of service to the Lord.

His testimony of compassion for broken men lives on in the Episcopal Cathedral’s stained glass window in Washington, D.C. Artist Lawrence Saint depicted John McIntyre, the redeemed drunk, with the lost sheep around his neck, according to Herbert Eberhardt’s 1957 article, “Rescue Mission Leaders.” John, a man with compassion and vision, served as president of the IUGM from 1919 to 1921, and as the chairman of the executive committee for 20 years.

Lucius B. Compton

Lucius B. Compton was a mountain boy from the hills of North Carolina. Crippled because of malnutrition, his family thought he was feeble-minded, and only permitted him fewer than six months of schooling. At 14, he left the hills to escape the law, and roamed from city to city, a boy tramp.

In Cincinnati, he was attracted by the singing at a mission and wandered into the service. After he became a Christian and started taking part in street meetings, his stuttering left him in an answer to prayer.

He eventually returned to Asheville and founded Eliada Orphanage and Home, a farm in connection with the home, the Faith Cottage Rescue mission, and a Bible conference grounds. He also became an internationally known evangelist. This unschooled mountain boy with a dream and a vision served as president of the IUGM from 1947 until his death in 1948, Herbert Eberhardt writes in “Rescue Mission Leaders.”